Category: News

By Professor Tommy Koh: Women’s Quest For Justice And Equality: A Short History

Women’s rights are human rights. The struggle by women for justice and equality is one of the longest in the history of human rights. Although much progress has been made, the struggle is not over in some parts of the world.

Boys and girls are born equal. Inequality sets in as they grow up. The causes are many, with history, religion and culture all playing a part.

In the ancient world, women were treated as chattel. They could be bought or sold. Women had to marry the men chosen for them. They had no legal personality. They could not own property. They had no freedom of movement. Men’s oppression of women is therefore an evil which has ancient roots.

Religion has generally reinforced gender inequality with precepts and doctrines that subordinate women to men. Some Christian denominations bar women from the priesthood or leadership positions. In Islam, women face restrictions on public prayer. According to some Buddhist text, women can attain Buddhahood only by first being reborn as men. In Hindu literature, women are depicted in a negative light, as being weak, sinful and irresponsible. The two religions which treat men and women equally are Sikhism and Bahaism.

Confucius taught that a daughter should obey her father, a wife her husband and a widow her son. Confucianism has had a pernicious influence on the status of women in Asia as it continues to influence the behaviour of men towards women in Northeast and Southeast Asia. The male chauvinist teachings of Confucius may be the reason why societies in these parts of Asia have such low fertility rates.

COLONIAL SINGAPORE

What was the situation in colonial Singapore? The British rulers of Singapore were all men. Reflecting the attitude back home, their attitude towards women was unenlightened.

Professor Aline Wong, in her book, Women In Modern Singapore, described the situation in colonial Singapore in the following way: “… the cultural traditions of the major ethnic communities in Singapore place a greater premium on the male compared to the female. Whether born as a Chinese, an Indian or a Malay, a woman is subjected to socio-cultural and religious pressures to conform to the roles of wife and mother and to lead a secluded life.”

Although several women’s leaders such as Shirin Fozdar, Seow Peck Leng and May Wong, had petitioned the British Governor and the British Parliament, to abolish polygamy, their petition was rejected. Chinese men were free to have as many wives and concubines as they wished. Women occupied an inferior status during British rule.

In 1877, the British Government established the Chinese Protectorate. Its objective was to look after the needs of the Chinese community. To its credit, the protectorate did try to tackle the problem of the trafficking of women and girls for prostitution. They also tried to ensure that the sale of young girls to rich families as “mui tsai” was not a form of slavery.

WOMEN’S CHARTER OF 1961

In its early days, the People’s Action Party (PAP) was a revolutionary party. In 1959, it campaigned for the policy of one man, one wife. In 1961, the Singapore government enacted the Women’s Charter. It was nothing less than the Magna Carta for women in Singapore.

What are the most important provisions of the Women’s Charter?

First, it abolished polygamy for all non-Muslim men and required that all future marriages be registered.

Second, a married woman could continue to use her own name.

Third, husband and wife were treated as equal partners in a marriage.

Fourth, women had the right to own, buy and sell property.

Fifth, the Charter safeguards the rights of women in matters relating to marriage and divorce.

Sixth, the Charter also protects the right of the wife to matrimonial assets, maintenance and the custody of children.

THE PAP AND WOMEN

In the 1950s and 1960s, the PAP had several women leaders such as Chan Choy Siong. It was a pro-woman party.

However, by the 1970s and 1980s, the PAP no longer had any women in its leadership. The party drifted away from its origin and became an anti-women party. Let me cite three examples to support my point.

- Quota For Women In Medical School

In 1979, the Minister for Health, Dr Toh Chin Chye, announced that women would be restricted to one-third of the intake for medical school. This unreasonable discrimination against women was abolished onlyin 2003. - Lower Admission Requirements For Male Students

In 1983, the National University of Singapore modified its entry requirements for male students. Why? In order to prevent any imbalance in the sex ratio in favour of women. Speaking in justification of this discrimination, the NUS President, Professor Lim Pin, said that a gender imbalance in the university would only aggravate the “problem of having unmarried graduate women”. - Home Economics Not For Boys

In 1984, the Ministry of Education stopped all Secondary I and Secondary II girls from taking technical studies. Henceforth, all girls had to study Home Economics and the boys had to take technical studies.

THE UNITED NATIONS’ POSITIVE INFLUENCE

Some foolish people think the world would be better off without the United Nations.

Without the UN, we would not have the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the Convenant on Social, Economic or Cultural Rights and, most importantly, the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW).

CEDAW was adopted in 1979 and came into force in 1981. Singapore became a party to the Convention in 1995.

Article 16 of CEDAW requires all State Parties to eliminate discrimination against women in all matters relating to marriage and family matters.

What are the rights of women protected by CEDAW? First, the right to freely and consensually choose her spouse. Second, to have personal rights to her children even in the event of divorce. Third, the right of a married woman to choose a profession or occupation. Fourth, to have property rights within marriage.

Before leaving the subject of the UN, I would like to acknowledge the important contributions which a Singaporean, Noeleen Heyzer, the former Head of UN Women has made.

In 2000, Dr Heyzer succeeded in persuading the UN Security Council to adopt resolution 1325. The resolution calls on states to safeguard the rights of women and girls in armed conflict. Judge Navanethem Pillay of the International Criminal Tribunes for Rwanda said:

“From time immemorial, rape has been regarded as one of the spoils of war. Now it is a war crime. We want to send out a strong message that rape is no longer a trophy of war.”

STATUS OF WOMEN IN SINGAPORE

Has Singapore women succeeded in achieving justice and equality with men? I think it would be fair to say that in most important respects, women have achieved equality with men.

Our women have achieved parity with men in education at all levels. Women’s participation in our workforce is at 42 per cent but there is still a wage gap between men and women.

Women outlive men. Most glass ceilings impeding the rise of women in Singapore have been broken. We have a woman as our President. We have several very capable woman ministers, permanent secretaries, judges of the Supreme Court, CEOs of statutory boards and leading corporations.

The only two areas which need improvement are the number of women in Parliament and the under-representation of women on corporate boards and in senior decision-making positions.

The world has recognised the tremendous progress which women in Singapore have achieved in the past 50 years. In 2016, the UN Human Development Report, ranked Singapore No. 11 out of 159 countries on its Gender Inequality Index.

In 2017, the US News and World Report, published a list of the 23 best countries in the world for a woman to live in. Singapore was ranked No. 22.

Women’s quest for justice and equality has made tremendous progress in the past few decades. In Singapore women have largely achieved parity with men. The Singapore Council of Women’s Organisations and the Association of Women For Action and Research should be acknowledged for their pivotal role in fighting for equal rights.

Singapore has become one of the world’s most women-friendly countries. However, women in some other parts of the world are not so fortunate. They are still treated as second class citizens and continue to live under the oppression of men. The struggle is not over.

By Professor Tommy Koh: Singapore and the United Kingdom: 1819 to 2019

On Jan 29 1819, Stamford Raffles, accompanied by William Farquhar and a small entourage arrived in Singapore. His objective was to establish a port and trading station for the East India Company. This is the beginning of the story of modern Singapore.

Our founding Prime Minister, Mr Lee Kuan Yew, held this view. Speaking to the Singapore International Chamber of Commerce on Feb 6 1969, Mr Lee said:”But for the wisdom and foresight of the Englishman with whose name the history of modern Singapore will always be associated, your Chamber, you and I, all of us would not be here today.”

Singapore’s founding fathers were famous for many things. One them was their disdain for political correctness.

They preferred the truth to fashion and never shied away from defying convention.

On Aug 8, 1969, a state banquet was held to celebrate both National Day and the 150th anniversary of the founding of modern Singapore. Princess Alexandra was among the invited guests, representing the British royal family.

Speaking at the banquet, Mr Lee said: “… we deem ourselves amongst the fortunate few who can afford to be proud of their past, with no desire to rewrite or touch up the truth. It is a short history, 150 years, but long enough for us to value our association with the British people.”

BICENTENNIAL BOOK

Singapore and the United Kingdom have a 200-year-old relationship. To commemorate the bicentennial, my friend, Scott Wightman, the British High Commissioner, and I have co-edited a book, entitled 200 Years of Singapore and the United Kingdom. It will be launched today (29 Jan), by Grace Fu, the Minister for Culture, Community and Youth. The purpose of this book is to undertake a balanced and objective review of the past 200 years, to draw some lessons from history and to think about the future. The book is not an attempt to glorify British imperialism and colonialism or the British rule of Singapore. I am not an admirer of Professor Niall Ferguson. He argued in his 2002 book, Empire: The Rise and Demise of the British World Order and the Lessons for Global Power, that the British empire was the cradle of modernity. In 2017, the Indian politician and intellectual, Shashi Tharoor, published a book, Inglorious Empire. The book is about the British rule of India. Tharoor accuses the British of having destroyed India, economically, culturally and psychologically. I regard Tharoor’s book as a good counter to Ferguson’s book. It is also not the purpose of our book to deny that Singapore had a history before 1819. We acknowledge that Singapore had been settled, not continuously, but intermittently, since the 14th century. We have therefore included essays, by the historian, Kwa Chong Guan and the archaeologist, John Miksic, on Singapore’s pre-1819 history. In his speech to the Singapore International Chamber of Commerce on Feb 6 1969, Mr Lee said: “When Stamford Raffles came here 150 years ago, there was no organised human society in Singapore, unless a fishing village can be called a society.”TIME TO HONOUR FARQUHAR

Mr Wightman and I both feel that Raffles has been given too much credit and William Faquhar, the First Resident, too little for his contributions to the success of Singapore. Raffles was the visionary. Farquhar was the pragmatist who turned the vision into reality. No one did more for the success of Singapore, in the first four years, than Farquhar. Graham Berry has written an excellent essay to set the record straight. We hope that, in this Bicentennial Year, the Singapore Government will acknowledge our debt to Farquhar in an appropriate way.MILESTONES OF A 200-YEAR JOURNEY

Two hundred years is a long time. We are only able to select a number of key milestones and requested some experts to write on them. For example, we have an essay by Peter Borschberg on the two treaties of 1824: the Anglo-Dutch Treaty and the Crawfurd Treaty. It was under the Crawfurd Treaty that the British obtained sovereignty to Singapore. We have an essay by Kennie Ting on Singapore’s port city heritage. He is an expert on port cities and is the author of a new book, Singapore 1819: A Living Legacy. Farish Noor has written an important essay on migration and multiculturalism in colonial Singapore. When Raffles founded Singapore, he appealed to Chinese, Indian, Arab, Jewish, Armenian and Western traders and entrepreneurs to come to Singapore. Many answered his appeal. Farquhar was able to use his reputation and network to persuade Malays, Bugis, Javanese, Acehnese, Boyanese and Minans to join the settlement. Farish Noor concludes that due to the fact that the settlers came from so many parts of Asia, “they gave to the land that they would adopt as their home a multi-perspective worldview that would ensure that Singapore remain a hub in the globalised post-colonial world to come.” Other milestones covered in our book include the Indian Mutiny of 1915, World War Two, the Japanese occupation, Subash Chandra Bose and the Indian National Army, the rise of nationalism and anti-colonialism, the political developments between 1945 and 1963 and from 1965 to the present. On the topics of merger and separation, we decided not to request two Singaporeans to write on them as we are all familiar with the Singapore narrative. To add value, we decided to invite two British historians, A J Stockwell and Nicholas J White, to do so. There is also a noteworthy essay by J Y Pillay on the decision by the British Government to withdraw from its military bases in Singapore by 1971. This was a big blow to the newly independent government, which was faced with high unemployment and the lack of job opportunities. It was estimated at the time that the withdrawal would mean the loss of about 10 per cent of our Gross Domestic Product. Miraculously, Singapore survived this early setback. The story is worth telling.THE BRITISH LEGACY

The biggest chapter of the book is on the British legacy in Singapore. We have many good essays on the English language, the rule of law, the free port, free trade, open economy, the civil service, health, education, welfare, town planning, low-cost housing, anti-corruption, business, sports, culture, the commonwealth, etc. The British left a rich legacy in Singapore. However, it is fair to say that, in many instances, the British had laid the foundation but, it was the government of independent Singapore which got the job done. This is true in the fight against corruption, in town planning, in the building of low-cost housing, in diversifying the economy, in cleaning and greening the city, etc. Irene Ng and Alan Hunt have written about the transformation of the relationship between Singapore and Britain, from 1965 to 2019. Foo Chi Hsia and Scott Wightman have written about the future of our relationship, post-2019.A PERSONAL REFLECTION

I was born and grew up in colonial Singapore. Colonial society was both racist and hierarchical. The whites were first class citizens. The Eurasians were second class citizens. The rest of us were third class citizens. The British colonial administration in Singapore did not observe the democratic norms and freedoms which the British citizens enjoyed at home. Any one deemed to be critical of or disloyal to the British could be banished to the land of his or her birth. I personally experienced censorship, for the first time in my life, when I was a student at Raffles Institution (RI). I had submitted two articles to the school magazines, one against apartheid in South Africa and the other criticising the way in which our hawkers were being hounded by the police. The school submitted my essays to the Ministry of Education, which decided that they could not be published. To be fair, I must also say that there were many good people from Britain who were working in Singapore, as doctors, lawyers, engineers, architects, teachers, etc. In RI, I had several expatriate teachers. I remember three of my teachers, Mr T J Evans, Mr J T Lippit and Mr W T Andrews, with respect and gratitude. To sum up, I would say that the British rule of Singapore was 60 per cent good and 40 per cent bad. However, compared to the other colonial rulers in Southeast Asia, the British were the least bad. The British left us with a rich legacy. We were able to build on that legacy and to catch up with and even surpass Britain in some respects. Over the past 200 years, the relationship between us has been transformed from that between the ruler and the ruled, between a rich and a poor country, between a developed and a developing country, into a relationship between two equals. When Britain leaves the European Union on March 29 this year, it will be in uncharted waters. I want to say to our British friends that they have our goodwill and support in their new journey. I have a final thought. I think we should remember the hardwork and sacrifice of generations of Singaporeans. It is the collective efforts of these people, over the past 200 years, which have produced the success story called Singapore.An interview with Jeremy Fernando in Clarín

In November 2018, whilst at the 4th Bienal de la Imagen en Movimiento (Moving Images Biennale) in Buenos Aires, Jeremy Fernando was interviewed by Carolina Keve of Clarín about his relationship to art, to writing, and to thought. In it, he attempts to “disarm the role of the author in order to place it on a more democratic plane.”

To read the interview, please go to https://www.clarin.com/revista-enie/ideas/escritura-hora-duelo_0_xqBGrfbCb.html

Clarín is the largest newspaper in Argentina.

2 talks by Jeremy Fernando at the Central Public Library

1. reading | art | resistance

Wednesday, 20 February

7pm

In this performance-talk, Jeremy Fernando will attempt to respond the possibility of art as resistance — that is, meditate on the possible relationship between resistance and art. And he will do so whilst foregrounding the fact that if art is the openness to possibilities, nothing can be known until it happens; after which it still quite possibility remains beyond cognition. Thus, the only thing one can do, is to resist what one thinks art itself is; and to read the work, attempt to encounter the work. As part of his performance, he will be showing works — from Singapore and beyond — that he thinks demonstrate possibilities, stage resistances.

To register: https://www.nlb.gov.sg/golibrary2/e/alt-txt-reading-art-resistance-71357805

2. writing | walking | blindness

Wednesday, 27 February

7pm

In this performance-talk, Jeremy Fernando will attempt to attend to the relationship between walking and thinking — movement and thought — through the all-too-familiar situation, scenario, of writer’s block. It opens with a meditation on the very moment he was unable to write — alongside the irony of writing about it. Which suggests that this writing — perhaps all writing — is an act of memory: one that is unable to account for the possibility of forgetting — and, thus, also fictionality. And in that spirit, he will offer the possibility that a painting — ‘Squid Love’ by Yanyun Chen — is the site through which this piece has been inked.

To register: https://www.nlb.gov.sg/golibrary2/e/alt-txt-writing-walking-blindness-58370953

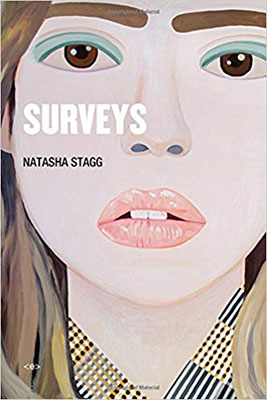

Tembusu Reading Pods AY2018/19 Sem 2

Register by 20 Jan 2019

Care to read and discuss a book outside your curriculum this semester? Simply choose one of the six titles offered by students and faculty of Tembusu College and register via Eventbrite (click on the link) by 20th January 2019, Sunday.

An email will be sent to all participants after 20th January to confirm their registration. The reading pod facilitator will contact participants via email to provide more details (starting date and venue).

Participants will be responsible to purchase their own book; eBook is accepted. The first 5 sign-ups are eligible for the subsidy (You need only pay S$10 for the book of your choice); participant should submit a RFP form with receipt attached to the college office for reimbursement of their purchase (e.g. book purchased at $15, college will reimburse $5). Subsequent sign-ups are welcome.

Click on the images for more information.

By Professor Tommy Koh: Asean and the UN: Natural partners

The United Nations (UN) and the Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN) are natural partners.

This is reflected in the charters of both organisations. In the case of the United Nations, Article 52 of its charter makes references to the role of regional arrangements or agencies in the maintenance of international peace and security. As for Asean, Article 2 (2) (j) of its charter commits Asean and its members to uphold the UN charter.

HISTORY

Asean’s relations with the UN began in the early 1970s through the UN Development Programme (UNDP), the development arm of the world body. The UNDP sponsored a two-year study to assist Asean in conceptualising its economic cooperation activities. As Asean began to make enormous progress in its economic development and rose to become a significant player in the international system, the relationship was transformed. The UN was no longer represented by the UNDP but by its Secretary-General.SUMMITS AND MINISTERIAL MEETINGS

The first ASEAN-UN Summit was held in 2000 in Bangkok, laying the foundaton for a growing network of stronger linkages and diverse areas of cooperation in the years to come. The second summit was held in 2005 at the UN’s headquarters, in New York. It was attended by the UN Secretary-General and the heads of the various UN bodies. In 2007, a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) between Asean and the UN was signed in New York, establishing a partnership for cooperation in many fields. The third ASEAN-UN Summit held in Hanoi, Vietnam, in 2010. At the meeting the leaders reaffirmed their commitments to working more closely in addressing issues of common concern such as the global financial crisis, climate change and disaster management. Asean-UN cooperation was reinforced at their fourth summit in 2011 in Bali, during which the leaders adopted the Joint Declaration of the Comprehensive Partnership between ASEAN and the UN. Areas of cooperation include maintaining and promoting regional peace, security, and prosperity. Subsequent years saw summits being held in Brunei (2013), Naypyitaw in Myanmar (2014) and Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia in 2015. The eighth summit was held in 2016 in Vientiane, Laos. At that meeting the Leaders approved a Plan of Action for the period 2016 to 2020 to implement the comprehensive partnership. Implementation of the plan is well underway, especially following the institutionalisation of the Secretariat-to-Secretariat mechanism in 2017. In addition to the summits, there is an annual meeting between the ASEAN Foreign Ministers, the President of the UN General Assembly and the UN Secretary-General during the High-Level Week in New York. This annual meeting is both substantive and symbolic. It reflects the close partnership between ASEAN and the UN as well as the high comfort level among their leaders.OBSERVER STATUS AT THE UN

In 2006, the UN granted Observer Status to ASEAN. In keeping with Asean’s frugal and pragmatic culture, the regional grouping has chosen not to have a permanent observer mission to the UN. However, the ASEAN New York Committee (ANYC), which comprises the 10 ASEAN missions to the UN, plays an active role in New York. It meets regularly to discuss issues of common concern, deliver joint statements and engage with its external partners. Under Singapore’s ANYC Chairmanship in 2018, Asean engaged with the leadership of the UN as well as with external partners such as the United States and Russia.A HELPING HAND IN ADVERSITY

A friendship is tested in times of adversity. In 2004, the Indian Ocean Tsunami brought death and destruction to Indonesia, Thailand and, to a lesser extent, Malaysia and Myanmar. The UN Secretary-General sprang into action and mobilised the resources of the UN system and the international community to help the affected countries. It was a shining example of cooperation between ASEAN and the UN. In 2008, Myanmar was hit by a killer cyclone called Nargis. It killed 140,000 people, destroyed 700,000 homes and devastated the padi fields of the productive Irrawaddy Delta. Myanmar faced a major humanitarian crisis. At first, the Myanmar Government was unwilling to open its doors to foreign assistance, fearing that certain Western governments would take advantage of the crisis to interfere and change its regime. ASEAN assured Myanmar that this would not happen. In the end, Myanmar agreed to accept international assistance, under the framework of the ASEAN-Myanmar-UN Tripartite Core Group. The cooperation between ASEAN and the UN in helping Myanmar to recover from the destruction of Cyclone Nargis, is a success story.UN PEACEKEEPING

One of the UN’s most important contributions to international peace is the role of UN Observers and Peacekeepers. The blue beret worn by soldiers and police officers serving under the UN flag, is a symbol of peace. Over the years, ASEAN members have contributed 4,500 personnel to various UN peacekeeping and observer missions. The UN has established peacekeeping training centres in six ASEAN countries. All 10 ASEAN countries have supported Secretary-General Antonio Guterres’ new Action for Peacekeeping initiative.SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT

The UN’S 2030 Agenda consists of 17 goals to promote sustainable development. These goals acknowledge that plans to promote economic growth must also address social needs such as education and health as well as the need to protect the environment for future generations. ASEAN supports the UN’s 2030 Agenda which complements the ASEAN Vision 2025. The commonality is the imperative to embrace sustainable development and to save the world from a looming environmental crisis. Thailand, as the next ASEAN Chair, has chosen “Advancing Partnership for Sustainability” as the theme of its Chairmanship in 2019.PREAH VIHEAR TEMPLE

I want to refer to a case of a threat to international peace and the cooperation between ASEAN and the Security Council in defusing it. Fighting between Cambodia and Thailand, along their border in the vicinity of the Preah Vihear Temple, had occurred between 2008 and 2011. When negotiations failed and the fighting continued, Cambodia brought the case to the attention of the UN Security Council. The then Chairman of ASEAN, Indonesia, spoke to the council on what ASEAN, in general, and Indonesia, in particular, had been doing to stop the fighting and to bring the two parties back to the negotiating table. In the end, the Security Council decided to outsource the problem to ASEAN. Peace was finally restored when Cambodia asked the International Court of Justice (ICJ) to interpret its 1962 judgement, awarding sovereignty over the temple, to Cambodia. The ICJ is incidentally, the judicial arm of the UN system.ASEAN-UN RESOLUTION

Since 2003, the UN membership adopts by consensus a biennial resolution welcoming cooperation between the UN and ASEAN. In addition, a one-off resolution commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of ASEAN was adopted by the General Assembly in 2017, the first of its type. These resolutions have been co-sponsored by a large number of countries, which show the wide support that ASEAN enjoys at the UN. On 11 April 2018, an important meeting was held in Jakarta, between the 10 ASEAN Permanent Representatives, called the Committee of Permanent Representatives to ASEAN or CPR, and the United Nations. The UN was represented by Assistant Secretary-General, Miroslav Jenca.MUTUALLY REINFORCING TIES

The Chairman of CPR, Ambassador Tan Hung Seng of Singapore, said that ASEAN and the UN are both committed to upholding the fundamental principles of sovereign equality, respect for international law and a rules-based international and regional order. Ambassador Jenca agreed and emphasized the importance of multilateral institutions like the UN to ASEAN. Singapore’s Permanent Representative to the UN and the current Chair of the ASEAN New York Committee, Ambassdor Burhan Gafoor, noted that the relationship between ASEAN and the UN is a mutually reinforcing one. The UN provides the multilateral rules-based framework that allows regional organisations like ASEAN to function effectively. At the same time, ASEAN contributes to global peace and security by strengthening habits of cooperation and respect for international law at the regional level. In conclusion, I wish to quote the words of the Foreign Minister of Singapore, Dr Vivian Balakrishnan. Speaking to the UN General Assembly this year, Dr Balakrishnan said: “Our work in ASEAN is rooted in our belief that regional organisations can demonstrate how multilateralism continues to be relevant and beneficial for people all over the world”.By Professor Tommy Koh: Asean and China: Past, present, future

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) was established in 1949. The Association of South-east Asian Nations (Asean) was created in 1967. From 1967 to 1978, relations between the PRC and Asean were difficult. During that period, the PRC sought to export communism to the Asean member states by supporting local communist insurgencies. Beijing also appealed to the ethnic Chinese population in Asean to support the PRC. Two Chinese leaders, Deng Xiaoping and Zhu Rongji, brought about a fundamental change to the relationship, moving it from night to day and from sour to sweet.

Changes under Deng and Zhu

In 1978, Mr Deng visited three countries in Asean – Thailand, Malaysia and Singapore. As a result of what he heard from the leaders of these countries, he stopped supporting the communist insurgencies, stopped the hostile radio broadcasts and stopped appealing to the ethnic Chinese population. For 30 years, from 1978 to 2008, China pursued a policy of good neighbourliness towards Asean. Gradually, trust replaced mistrust and the relationship steadily improved. Mr Zhu Rongji was the premier of China from 1998 to 2003. He was a brilliant man and a strategic thinker. He wanted to bring Asean and China closer to each other by linking their economies. In 2000, he offered Asean a free trade agreement. Asean accepted his offer in 2001. He also offered Asean an early harvest, meaning that even before the conclusion of the FTA, some Asean exports were given tariff-free access to the Chinese market. The conclusion of the Asean-China Free Trade Agreement (ACFTA) has transformed the character of the relationship between Asean and China.

Nature of current relationship

China became a dialogue partner of Asean in 1991. In 2003, the relationship was elevated to a “strategic partnership”. China appointed an Ambassador to Asean in 2012. The current relationship is both broad and deep. The two sides enjoy many points of convergence and a few points of divergence. I will proceed to review the different sectors in which the two sides cooperate to their mutual benefit.

Economic Cooperation

The economic relationship is very impressive. China is Asean’s top trading partner and Asean is China’s No. 3 trading partner. Asean is China’s top foreign investor and China is Asean’s No. 3 foreign investor. The two-way trade in 2017 was US$441.6 billion (S$607 billion). China accounts for 17 per cent of Asean’s external trade. To enhance economic cooperation, China has hosted, since 2004, an annual China-Asean Expo in Nanning. In 2015, Premier Li Keqiang and the 10 Asean Leaders signed a protocol to upgrade the Asean-China FTA. Asean, China and five other dialogue partners are currently seeking to conclude the 16-party Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement. Cooperation has expanded into many new areas. This year, we successfully concluded the Asean-China Year of Innovation. There is demand in Asean for innovative technology, and China has many high-tech solutions.

Political and Security Cooperation

Asean and China share the objective to promote peace and stability in the Asia-Pacific. They seek to build a regional order which is transparent, inclusive and rules-based. China’s leaders have consistently expressed support for the central role which Asean plays in the regional architecture. Asean and China cooperate in various forums, including, Asean + China, the Asean Regional Forum, Asean + Three (China, Japan and Republic of Korea), the East Asia Summit and the Asean Defence Ministers Meeting Plus. In October last year, Asean and China carried out, for the first time, a joint maritime exercise. The exercise took place in Singapore and in China. The exercise in Zhangjiang, China, involved all 11 countries (the Asean 10 and China) as well as more than 1,000 military personnel. It was successful and a positive contribution to confidence building.

People-to-People Cooperation

The good relations between Asean and China must rest on three pillars: government, business and the people. Tourism is booming between Asean and China. In 2016, close to 20 million Chinese visited the Asean countries and over 10 million Asean nationals visited China. A joint statement between Asean and China on tourism cooperation was adopted by Asean and China last year. Air links between the two sides are growing. At present, there are nearly 50,000 flights per week between 37 cities in Asean and 52 cities in China. The exchange of students is also expanding. It is estimated that there are about 200,000 students from the two sides studying at each other’s universities.

AIIB and BRI

Asean has been a dependable friend of China. Let me cite two examples. In 2013, China proposed setting up the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). It was intended to be a multilateral development bank, focusing on the building of infrastructure in the Asia-Pacific region. The AIIB has 87 members and began operation in 2015. All 10 Asean members are founding members of AIIB. In late 2013, President Xi Jinping launched a new initiative called the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road. The initiative is now known as the Belt and Road Initiative or BRI. The concept is to rebuild China’s ancient connections to the West, by land and sea. The initiative has been described as one of the largest infrastructure and investment projects in history, involving 68 countries, including 65 per cent of the world’s population and 40 per cent of the global GDP. Asean has supported the BRI from the onset. However, Asean would like the BRI to complement and not supplant the Master Plan on Asean Connectivity 2025.

South China Sea

Asean and China have both convergent and divergent views on the South China Sea. Asean holds the view that the South China Sea is a vital sea line of communications of the world. It is, therefore, a global commons and cannot be appropriated by any state. Asean is also of the view that the South China Sea is governed by international law, including the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea. All the claimant states and the user states should act strictly in accordance with the law. Asean holds the position that disputes relating to the South China Sea must be settled peacefully, in accordance with international law. If negotiations fail, the parties to a dispute should be willing to refer their cases to a binding dispute settlement procedure, such as, conciliation, arbitration or adjudication. China is a claimant state. Four of the Asean members – Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines and Vietnam – are also claimant states. Asean is not a claimant state and does not take sides regarding the merit of the various claims. But it is a stakeholder. It has a stake in peace in the region, in the freedom of navigation and overflight and in upholding the rule of law. In 2002, China signed the Declaration of Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea. In 2011, the two sides adopted the guidelines for the implementation of the declaration. In 2016, the foreign ministers of the two sides adopted a joint statement to ensure the full and effective implementation of the declaration. In 2017, Asean and China announced the commencement of the negotiations of the Code of Conduct in South China Sea. This year, the two sides arrived at a single negotiating text, which would be the basis of further negotiations. Given goodwill on all sides, it should be possible to make further progress towards resolving outstanding issues of its geographical scope, whether the code will be legally binding and whether to include dispute settlement.

Evolving ties

The relationship between Asean and China has gone through three historical phases. It has transitioned from hostility to amity to uncertainty. Why uncertain? Because China is now a rich and powerful country. The question is whether such a China will continue to pursue a policy of good neighbourliness towards Asean and its member states. I am optimistic. I believe that it is in China’s national interest to have good relations with Asean and with its neighbours in South-east Asia.

Tribute to Prof. John Richardson

Tembusu College expresses its heartfelt sympathy to our friends at Cinnamon College for the loss of their founding Master, Prof. John Richardson. John was a friend and close colleague of mine, first during the four years we worked together in the FASS Dean’s Office, and later when we became the first Masters of, respectively Cinnamon and Tembusu colleges. Tembusu actually began in an office in the “Old Administrative Building” (now demolished) which then housed the USP Programme, and which John graciously loaned to us during our planning year of 2010. In 2011, John and I walked together across the bridge over the AYE, along with students from our two colleges, to joyously open UTown.

John was a passionate advocate for his programme, and his college. The two colleges were friendly rivals in those first few years, but John and I always respected one another, and cooperated to keep things steady. Once, when a dispute between student leaders at the two colleges threatened to get out of hand, John and I arranged to very publically have dinner together in the middle of the our shared dining hall to cool tensions and demonstrate our friendship. I like to think the current good and easy relations between Cinnamon and Tembusu were forged through such mutual efforts in our early years.

John was tough-minded, but also self-deprecating, reflective, and possessed of a sense of humor. He did his best at every task, and for that reason was given many responsibilities over the course of his career at NUS. It is no exaggeration to say that John gave his life to this university. His passing was a shock, and came too early. But I’m truly glad to have known and worked with John Richardson, and will cherish his memory.

Gregory Clancey, Master, Tembusu College